Tarantula Molting Process

Reviewed by Petco’s Animal Care, Education and Compliance (ACE) Team

As pets, are relatively docile, friendly and low-maintenance. Unlike most pets, however, spiders—including tarantulas—are unique in that they periodically molt their outer covering. To molt properly, tarantulas must be provided with the proper conditions in their habitats and enclosures.

Like all spiders, tarantulas have a hard exoskeleton. Unlike a mammal’s internal skeleton, which gets bigger as they grow, a tarantula’s exoskeleton doesn’t grow with the spider. Tarantula molting is how a growing spider sheds its old exoskeleton. Molting is fascinating to watch, but it’s also a vulnerable time for your spider—so understanding tarantula molting care is essential. Check out our Tarantula Care Sheet to learn how to keep your spider healthy and happy.

How often do tarantulas molt?

How often tarantulas molt depends on their age and species, as well as factors like food quality and their habitat’s humidity levels. Pets given high-quality food and housed under proper conditions are generally healthier and grow more quickly, which means they may molt more frequently than unhealthy tarantulas. Some species of tarantulas grow faster or larger than others and will also molt more frequently.

Typically, young tarantulas molt about once every one to three months, while adults molt once or twice a year. Toward the end of their life span, tarantulas shed less frequently and may go for years without molting.

Exactly how long does it take a tarantula to molt? Depending on their age and size, the tarantula molting process can take as little as 15 minutes or as long as 12 hours. If your spider takes longer than 15 hours to molt, they may be experiencing tarantula molting problems and should be examined by a veterinarian.

Pre-molting changes

Whether you keep a curly hair, Chaco golden knee, Mexican red knee or Chilean rose hair, the molting process is the same for all tarantula species. But how do you know when a tarantula is going to molt?

The first sign of tarantula molting behavior is lack of appetite and a change in activity level. Before a molt, tarantulas typically stop eating and moving about their habitat—or they will move more slowly. Adult tarantulas may stop eating for up to three months before a molt.

Next, ttheir exoskeleton—or carapace—becomes transparent, except for a bald spot they develop on their abdomen that becomes progressively darker as they start to molt. A molting tarantula may also spin a unique web—called a molt mat—where they can be comfortable during the molting process. Finally, their exoskeleton starts to peel away and the spider turns onto their back with their legs outstretched, ready for molting to begin.

What to do when molting starts

The tarantula molting process begins naturally. Once you see the molting signs, clean their habitat and provide fresh substrate and bedding, as tarantulas are more prone to infection during molting.

Remove any leftover food in their habitat, and ensure they have access to plenty of fresh water—hydration is vital for a successful tarantula molt.

Finally, ensure that their habitat is at the right temperature and humidity level. Depending on the species, tarantulas should be maintained within a temperature range of 68 to 82°F and at a humidity of 40% to 90%. Spray the habitat with water to increase humidity, as many spiders benefit from increased moisture levels during this time.

How does tarantula molting appear?

The process can look strange, and it’s sometimes hard to tell whether a tarantula is molting or ill. What’s so odd about it? First is the tarantula molting position—adult spiders will lie on their backs for 12 to 24 hours, first without moving, and then they’ll kick their legs while casting off their exoskeletons. This activity helps distinguish molting from illness, as a dying tarantula stays on its stomach and curls its legs underneath itself rather than kicking.

As the tarantula molting stages progress, the exoskeleton splits open at the abdomen and the spider starts pushing its new body through the hole. The spider wiggles their legs to pull them free from the discarded exoskeleton and move the old skin to the side. Although it may take time and successive molts, tarantulas can even regrow legs lost during molting.

What do I do after my tarantula molts?

When a tarantula’s molting process is complete, the spider may eat part of their old exoskeleton to help regain energy. Some tarantulas even cuddle with their exoskeletons. You don’t need to remove the molted skin right away, but you can use tweezers to remove it if you wish. You may even want to save it to track their growth.

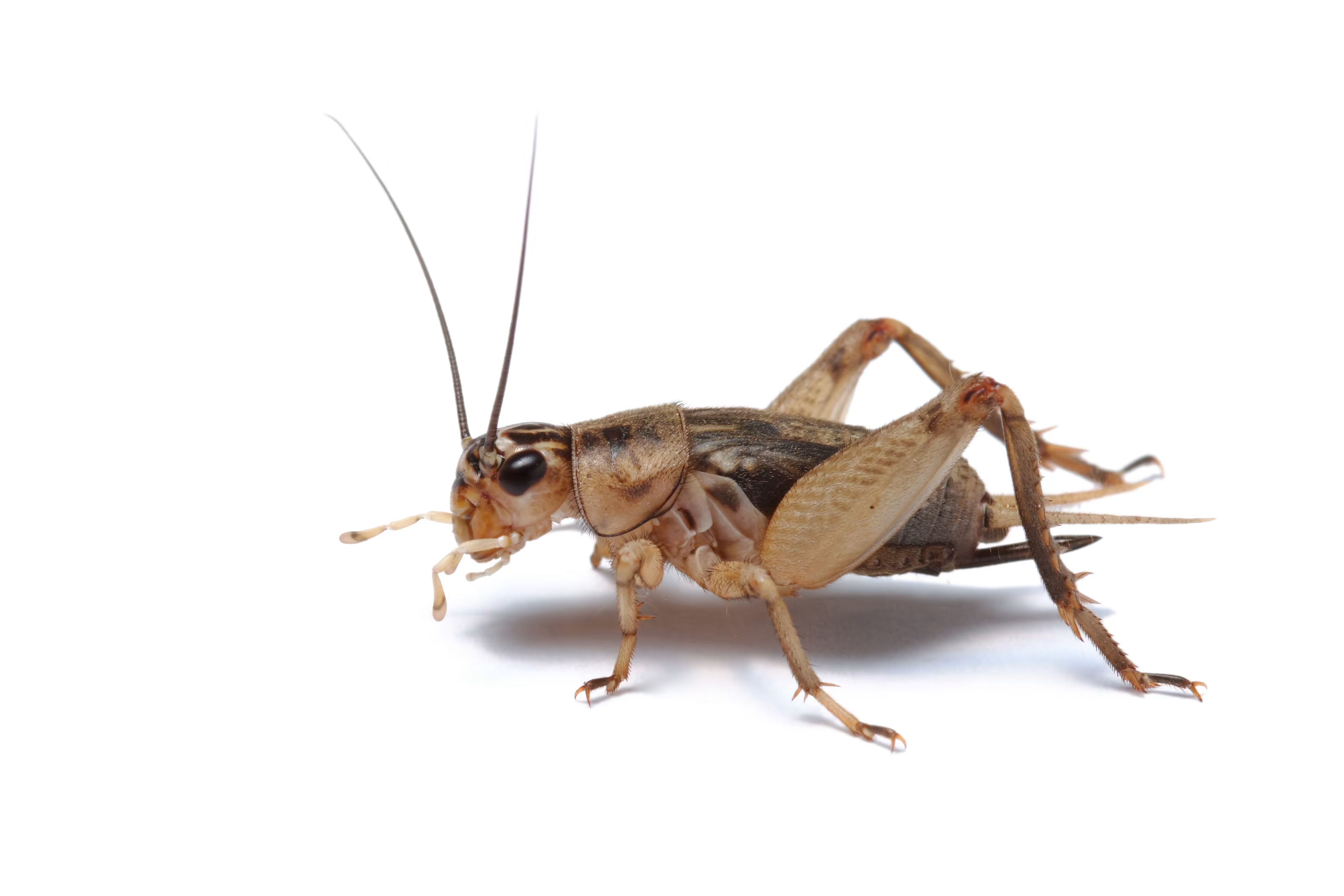

The new exoskeleton covering the tarantula is soft and takes several days to harden. For a week or two after molting, the tarantula is vulnerable to injury and should not be handled or fed crickets or other insects that could potentially bite and harm the spider All they need is fresh water and time.

Potential tarantula molting problems

While normal molting typically won’t hurt your tarantula, there is a small chance something could go wrong. Death is rare but not impossible. In fact, once males become fully mature, they may not survive their next shed. The most common problems to look out for during molting include:

Slow or asymmetrical molting

As they age, a tarantula’s molting time typically slows down—eventually, they may not survive the molt at all. Older spiders may take several days to complete a normal molt. However, they should make continual progress—moving their legs and working their way out of the old exoskeleton—even if progress is slow.

Healthy molting should take place symmetrically and should follow a particular order. First, the carapace opens and the chelicerae—or fangs—pop out. This is followed by the rest of the head—including the sucking stomach—then the front legs and the back legs. If the tarantula extracts one side of its body from the exoskeleton but not the other—or the back legs but not the front legs—there may be a problem.

Getting stuck

While slow molting isn’t always concerning in older spiders, tarantulas can sometimes get stuck inside their old exoskeleton. This typically happens with just a leg. If a larger body part becomes stuck, tarantula molting death can occur.

If you’ve noticed your spider has stopped moving or making an effort to molt, the spider could be experiencing tarantula molting problems. If your spider appears stuck in their old exoskeleton, try misting them gently with lukewarm water. The increased hydration may set them free. If that doesn’t help, you can wet a small paintbrush and brush away clinging unshed portions of exoskeleton.

Deformed legs

Pet spiders that lose or damage a leg during tarantula shedding typically survive—juveniles often injure their legs during their early molts as they get the hang of the process. However, leg loss or injury may affect their next molt. Legs that are injured or deformed—but don’t fall off completely—need to be removed, as they can cause even bigger problems during molting. Don’t worry—a tarantula’s leg will slowly regrow and eventually reach the same size as the other legs after successive molts.

The tarantula molting process is fascinating and typically does not harm the spider. To help your tarantula through molting, ensure they have proper habitat conditions and are well-hydrated. Monitor them to ensure they’re making progress, but only intervene when it’s clear they’re stuck. If you have questions or concerns, talk to your veterinarian.

Featured Tarantula Products

Reviewed by Petco’s Animal Care, Education and Compliance (ACE) Team

Petco’s ACE team is a passionate group of experienced pet care experts dedicated to supporting the overall health & wellness of pets. The ACE team works to develop animal care operations and standards across the organization and promote proper animal care and education for Pet Care Center partners and pet parents, while also ensuring regulatory compliance.

Related Articles

Related Questions

Sponsored

Two Easy Ways to Start Earning Rewards!

Become a member today!Members-only pricing and offers, personalized care notifications, Vital Care points back on every purchase and more!Become a credit card member today!

Earn 2X Pals Rewards points at Petco

when you use Petco Pay!APPLY NOWLearn More About Petco Pay Benefits